The Night a Cursor Learned to Listen

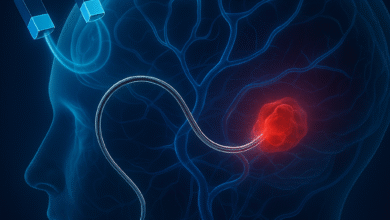

On a winter night in January 2024, a surgical robot—needle-fine, steady as a metronome—threaded 64 hairlike electrodes into the motor cortex of a young man named Noland Arbaugh. Minutes later, beneath the sterile lights of an operating theatre in Arizona, a coin-sized computer went silent and then awake, ready to translate thought into action. Elon Musk would soon call it “Telepathy.” The rest of us called it a line crossed: the first in-human Neuralink implant.

Arbaugh had lost nearly everything below his shoulders after a 2016 diving accident. For years, screens were barriers—useful worlds locked behind plastic. Then Neuralink arrived with a simple, audacious promise: think, and the cursor will obey. The company had secured FDA clearance to test its system, and Noland volunteered to be patient zero in the PRIME study. The goal was modest in phrasing—control a cursor or keyboard with thought—yet revolutionary in implication.

Recovery moved fast. Within weeks, the device was speaking his neural language: spiking patterns fired when he imagined moving his hand; software learned to map those signals into motion. And then, in March, Neuralink did something theatrical—they went live. The world watched as a cursor began to glide across Noland’s laptop. He opened a chessboard, hovered, clicked. Bishops flew; pawns marched. He grinned and said it felt “like using the Force.” The internet called it a magic trick. Engineers called it signal decoding. Either way, a barrier cracked.

Of course, firsts are messy. In the weeks after surgery, some of the ultrafine threads that carry electrodes into brain tissue subtly retracted—an engineering gremlin that reduced the number of active channels and, briefly, performance. Neuralink disclosed the issue, then pushed software updates and decoding tweaks that clawed back speed and accuracy. The human-machine duet resumed, stronger. This is how frontier tech always moves: one step forward, one stumble, then a sprint.

If you want to understand why this moment jolted even jaded neuroscientists, consider the choreography involved. Each thought of “move right” is not a word but a shimmering constellation of spikes across neurons. The implant samples and streams those signals wirelessly; algorithms guess intent in real time; the cursor obeys in under a heartbeat. It’s not the first brain-computer interface to reach a cursor—pioneers at BrainGate paved the way years ago—but Neuralink’s fully implantable, wireless package, robotic sewing method, and public demo compressed decades of promise into a single, cinematic reveal.

For Noland, the spectacle gave way to everyday superpowers. He could browse the web, text friends, even sink hours into online games without a mouth-stick or caregiver at his elbow. The difference wasn’t just speed; it was dignity—agency returned by silicon. Neuralink said he used the system for research sessions on weekdays and marathon play on weekends. He wasn’t a lab subject anymore. He was a user. Fierce Biotech

Skeptics are right to keep the champagne on ice. Stability over years remains unproven. Long-term safety, device removal, thread migration, battery longevity—open questions all. And ethics will loom larger as capabilities climb: privacy of thought, consent, dependency, access. But it’s also true that in a single season, the abstract future—hands-free computers for the paralyzed—became a person with a name, a laugh, and a killer opening in online chess. That matters.

By late 2024, Neuralink reported a second participant without the thread-retraction hiccup—evidence that hard-won lessons were already being built into the process. Progress in neurotech is iterative, and each iteration raises the ceiling for the next. Today a cursor; tomorrow maybe a robotic arm, or typed speech, or a smart home obeying silent intent. The slope is slippery—in the best way. Reuters

Call it spectacle if you like. The spectacle moved a cursor.

And somewhere in that motion, in the unremarkable act of clicking “play,” a door opened—quietly, thrillingly—into a new relationship with our own minds.

References

- Reuters: first human implant announced (Jan. 29–30, 2024); patient controls a mouse; live chess demo. Reuters+2Reuters+2

- The Guardian & The Times: livestreamed chess; patient quotes and context. The GuardianThe Times

- Neuralink official updates: PRIME study progress; thread retraction disclosure; 100-day update. Neuralink+1

- Reuters/FierceBiotech: post-op thread retraction issue and mitigation. ReutersFierce Biotech

- Reuters: second participant without retraction issue (Aug. 2024).